I’m grateful to my fellow amateur historian Debbie Kirk for alerting me to the fact that John Chapman and Peter André’s 1777 map of Essex has now been digitised and can be accessed online.

As Andrew McNair explains on his website dedicated to the map:

John Chapman was a land surveyor brought up in the village of Dalham in Suffolk who later came to work in London with Mrs Mary Ann Rocque, widow of John Rocque, the highly influential surveyor, engraver and cartographer. Chapman had previously been involved in producing county maps of Durham, Staffordshire and Nottinghamshire. He died the year after his Essex map was published. Peter André was of Huguenot descent, like many others involved in county surveys, and had gained experience of county surveys with his involvement in the publication of a map of Surrey. In summary the two surveyors were unusually proficient in surveys of large areas of land, such as counties; this probably explains why their Essex map is of exceptional accuracy and beauty…

Chapman and André’s survey of Essex was the first map of the county that allowed contemporaries to place their village, local market town and even their own house within the immediate landscape. Surveyed at the unusual scale of two inches to the mile it contains a wealth of detail that earlier maps did not even attempt to portray and it predates the Board of Ordnance (later the Ordnance Survey) by almost forty years. It was one of a series of county maps published by private cartographic entrepreneurs in the second half of the eighteenth century and because it was surveyed before Parliamentary Enclosure it records landscape features that were to disappear over the subsequent five decades.

It’s a wonderful map, and a fantastic resource for researchers: I’m certainly going to find it useful as I continue to explore the lives of my ancestors in Barking, East Ham and elsewhere in the county.

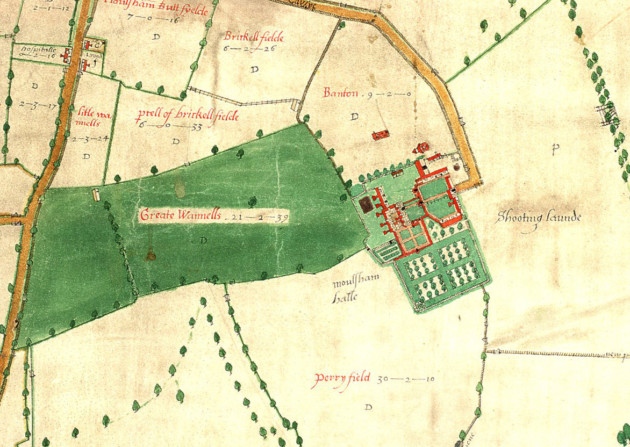

But my first thought on viewing the map was that it provides us with intriguing new insights into the history of Moulsham, and particularly of Moulsham Hall. In previous posts on this blog, I’ve relied mainly on early Ordnance Survey maps in trying to align modern Moulsham with the landscape of the past, and in attempting to locate the site of the hall. Some time ago I came across a map from 1799, which provided some additional information, and of course there is the invaluable 1591 map by John Walker.

However, Chapman and André’s map presents us with a uniquely clear and detailed image of what Moulsham, and particularly the hall and its park, looked like in the middle of the eighteenth century, before the land started to be sold off and the buildings demolished. We can see clearly the extent of the estate, its boundaries, and the location of buildings and gardens – making it easier than ever before to relate Moulsham past to Moulsham present.

Before looking more closely at the map, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the contemporary context. In 1777, George III was on the throne, Lord North was prime minister, and the American Revolutionary War was at its height. Closer to home, it was nearly half a century since Benjamin Mildmay, Earl Fitzwalter, had inherited Moulsham and proceeded to tear down his ancestors’ Tudor home and rebuild Moulsham Hall in the fashionable Palladian style. In 1756 the estate had passed to his cousin, Sir William Mildmay, who married his cousin Anne, daughter of Humphrey Mildmay of Hampshire. On William’s death in 1771 Anne inherited all of his properties, including Moulsham.

I believe that Anne is the ‘Lady Mildmay’ whose name appears on Chapman and André’s map, beneath the name of Moulsham Hall. She remained its owner until her death in 1795, when ownership passed to yet another cousin, Jane Mildmay, the wife of Sir Henry Paulet St John, who added the surname ‘Mildmay’ upon marrying her. He would be the last owner of Moulsham Hall, until its sale and demolition in 1816.

In 1777, all of that was still decades away, and the map shows Moulsham Hall and its estate in its Georgian heyday. It’s interesting that the park surrounding the hall is much more extensive than it would be even in 1799. If you want a detailed sense of how the eighteenth-century landscape of Moulsham relates to today’s densely-populated suburb, then I recommend looking back over the earliest posts on this blog. However, suffice it to say that the brown-coloured road running from north-east to south-west to the left of the Moulsham estate corresponds roughly to today’s Moulsham Street, as it runs out of the town in the direction of London. The road that leads off from it, before it reaches Widford, and passes by the edge of Thrift Wood, before touching the south-western tip of the Moulsham Hall park, follows the route of the modern Wood Street. As I’ve noted before, the sharp dog-leg turn when it reaches the top of the hill can still be found, where Wood Street forms a junction with Longstomps Avenue and Galleywood Road. In fact, that familiar sharp-angled turn, today marked by a mini roundabout, has been there in some form since John Walker devised his map in the reign of Elizabeth I.

On the 1777 map the eighteenth-century equivalent of Galleywood Road continues south past Tile Kiln Farm, just as today it passes by Tile Kiln Farm housing estate. We can see that the western boundary of Lady Mildmay’s park doesn’t coincide exactly with these roads. The area that today lies to the west of Longstomps Avenue and Vicarage Road was probably taken up by fields, also belonging to the Mildmay family.

The southern boundary of the park, certainly at its western edge, followed the line of the border between Moulsham Lodge and Tile Kiln Farm estates, which some of us can remember as a footpath extending as far as Beehive Lane. The park boundary deviates somewhat from this line as it extends eastwards, taking in a portion of what is now Tile Kiln estate. The fact that the familiar east-west ridge of high ground is clearly marked on the old map makes it easier to see how past and present landscapes relate to each other.

The eastern edge of Moulsham Hall park is more difficult to discern from the 1777 map, partly because it crosses the divide between two separate sections of the map. The boundary seems to run down the hill, through the middle of what is now Moulsham Lodge estate – perhaps following the line of what is now Gloucester Avenue or even St Anthony’s Drive – before striking out northwards towards Lodge Farm, of which all that remains today is the original Georgian house surrounded by new houses in Waterson Vale. The short road extending northwards beyond the lodge corresponds to modern-day Moulsham Chase. The road that crosses it a little further along is equivalent, as it runs westwards, to today’s Lady Lane which, as it approached Moulsham Street, may have joined with the end of what is now St John’s Road: it’s difficult to be precise, when so much has changed in the intervening two and half centuries.

Further east, what in 1777 was called Gravelwood Lane I take to correspond to present-day Beehive Lane. The bend in the road where the hilly ridge crosses it can still be seen near the junctions with Sawkins Avenue and Duffield Close, while the house that can be seen to the left of the road at this point on the map is represented today by the buildings occupied today by (according to Google Maps) The Window Company – but which, in my childhood, was still a farm – one that my father remembers visiting on business when he worked for a seed potato company in the 1960s – and marked as ‘Sawkins’ on nineteenth-century maps.

Moulsham Hall in 1776

So much for the boundaries of Moulsham Hall park. When we turn to the hall itself, we find Chapman and André’s map provides perhaps the clearest image yet of the buildings and gardens at the heart of the Mildmay estate. In previous posts I’ve argued that the large, square-ish field that was still visible on nineteenth-century maps, and whose outline could still be discerned in aerial photographs from as recently as 1935, marked the site of Moulsham Hall and its gardens and outbuildings. The left-hand edge of this field was bounded by the walled Moulsham Hall Gardens, which survived until their demolition in the early 1960s. These gardens can be seen clearly on the 1777 map, once again on the left edge of the square shape around the hall. At their northern end three small squares – additional gardens? – join them at a right-angle. The dark shape to the right of these squares represents the hall itself, with its circular drive way in front of it (clearly visible in the 1776 illustration reproduced above), and other paths leading off in various directions, presumably providing convenient walks around the immediate environs of the house. The map seems to confirm one’s intuition that the site of the hall lay somewhere between present-day Moulsham Drive, roughly where it meets Oaklands Crescent, and Fortinbras Way, opposite the entrance to Moulsham schools.

To the north of the house is the ‘large sheet of water’ described in a publication of 1809, together with a smaller pond, beside the path leading into the estate from Moulsham Street. This would have been a kind of ‘back entrance’ to the hall from the town, but a grander approach would have been by way of the winding drive through the park from the east, entering via the lodge. Visitors approaching Moulsham Hall from this direction would have seen the house and park in their full splendour.

I’m sure I’ll be returning to Chapman and André’s map in future posts, as it continues to offer new insights into the history of Moulsham.